Achieving equitable maternal health care is a priority that hospital leaders in Texas are stepping up to meet now more than ever. With the state making up 10% of all U.S. births, or nearly 380,000 annually, maternal health care in Texas is a national priority. And evidence shows that while Texas is making progress, it still has much work to do in the areas of maternal health care.

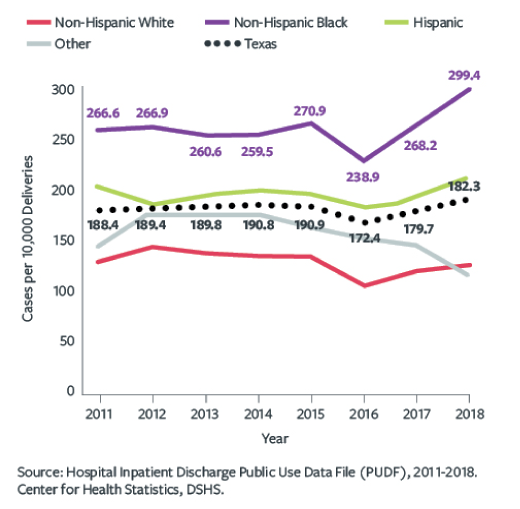

According to the 2020 joint biennial report from the Texas Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Review Committee and the Texas Department of State Health Services, the rate of severe maternal morbidity in Texas was 182.3 per 10,000 hospital deliveries in 2018. The report also showed that Black and Hispanic patients were more severely impacted by adverse health outcomes than their white counterparts. Black patients had higher and increasing rates of severe maternal morbidity from 2011-2018. In 2018, the rate of severe maternal morbidity per 10,000 hospital deliveries was 299.4 for Black women, an increase from 238.9 in 2016, compared to the overall rate of 182.3.

Yet, the data also show where Texas hospitals can improve to provide better, more equitable maternal health care. Underscoring the critical role of providers and hospitals in these inequities, the report found provider- and facility-related factors were frequent contributors to pregnancy-related deaths among non-Hispanic Black (56% of factors) and Latina women (50% of factors), as opposed to individual or patient-related factors.

Rate of Delivery Hospitalizations Involving Any Severe Maternal Morbidity in Texas, by Ethnicity

As part of the Healthy Texas Mothers and Babies Initiative, in December 2017 DSHS introduced TexasAIM to improve the quality of health care for pregnant women and new moms in Texas. TexasAIM participants use evidence-based practices and resources for treatment policies, safety equipment, training programs and internal reviews to address common maternal morbidity outcomes.

Manda Hall, M.D., oversees maternal and child health programming in the state as the Associate Commissioner of Community Health Improvement for DSHS. She says a critical component of the TexasAIM is the support hospitals receive in their effort to improve the quality of maternal health care: “We are supporting hospitals across the state of Texas and implementing quality improvement activities. And we do that through shared learning and collaboration across the state.”

TexasAIM resulted from the Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force’s (now named the Texas Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Review Committee) recommendation to implement the maternal patient safety bundles promoted and supported by the Alliance for Innovation in Maternal Health (AIM), the federally supported national program. TexasAIM began its work by focusing on obstetric hemorrhage as data show that this is one of the leading causes of preventable maternal mortality severe maternal morbidity.

TexasAIM hospital leaders said that the first step in implementing the TexasAIM bundle was evaluating extant resources and policies around improving quality for maternal health care, then building from there. Christina Davidson, M.D., is the Chief Quality Officer for Obstetrics and Gynecology at Texas Children’s Pavilion for Women in Houston and Vice Chair of Quality, Patient Safety and Equity for the Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology at Baylor College of Medicine. She said her organization’s first undertaking in adhering to the TexasAIM hemorrhage bundle was doing a gap analysis.

“That was the first step: sitting down and looking at the bundle and determining what was already in place in our hospital and what needed to be developed or enhanced and then implemented,” said Dr. Davidson.

To benchmark their progress and compare to national, state, and other hospitals’ data, Dr. Davidson and her team decided to measure severe maternal morbidity in accordance with the AIM-recommended Centers for Disease Control and Prevention codes. “Since, as a state, our goal was to reduce morbidity from hemorrhage by 25%, we decided to adopt that metric internally and abandon the composite metric we had been using that was unique to our hospital.”

Jeny Ghartey, D.O., M.S. is the Maternal Medical Director at Ascension Seton Medical Center in Austin where she says they issued a call to action in August 2020 to reduce severe maternal morbidity among their Black and Latina patients and compose the Health Equity Response, or HER, team to review severe maternal morbidity cases from the last two years and “identify areas of improvement and prospectively initiate and monitor the success of those changes from an anti-racist lens.”

They found their Black patients made up a disproportionate portion of hemorrhage and hypertension cases, the two primary causes of morbidity.

Dr. Ghartey said a key strategy they have implemented to address obstetric hemorrhage was assessing risk and treatment options upon admission to the hospital. “When patients are coming in, we’re identifying if they’re at risk for postpartum hemorrhage based on several factors. We’re trying to optimize their hemoglobin such that if they do experience blood loss in the delivery, which we know all women do, that they won’t be starting with a low hemoglobin count.”

“We are also standardizing our approach with how we measure blood loss at the time of delivery with the objective that a more accurate assessment of blood loss will lead to quicker reaction and response to postpartum hemorrhage,” said Dr. Ghartey. These approaches are applied to all of Ascension Seton’s sites “which helps to minimize the variation in care.”

“Now is the time to recognize the difference between equity and equality, in which care and treatment will vary by patient needs: That’s the difference with equity: figuring out what our patients’ unique needs are to give everyone the same outcome. They’re not all going to have the same outcome with the same exact treatment.”

TIFFANY RICKS, PH.D., RN, CO-FOUNDER OF ASCENSION TEXAS COUNCIL ON RACIAL HEALTH EQUITY

Reducing the variation in treatment for patients who present with complications by standardizing care leaves little room for provider bias and medical error, said Dr. Ghartey.

“I think we’re in a very unique time in our history where folks are receptive to hearing, learning and talking openly about structural racism and health inequity,” she said.

Texas is one of the most racially, ethnically and culturally diverse states in the nation, making measuring and tracking racial disparities in maternal health a foundational component in achieving equitable health care, interviewed leaders said.

Dr. Davidson at Texas Children’s Pavilion for Women says that three months into working on implementing the hemorrhage bundle they began tracking disparities in outcomes: “My quality team and I decided that we wanted to stratify our data by race, ethnicity and preferred language so that we could identify if disparities were present in severe maternal mortality and morbidity from a hemorrhage rather than just reporting on an aggregate outcomes for every woman who had delivered in the hospital.”

Almost immediately they saw that Black patients at their hospital were more likely to suffer severe maternal morbidity, compared to other patients. “No one wants to believe disparities exist in their hospital, but they probably exist in every hospital for us to have such disparate rates reported nationally and in Texas.”

“When you realize it’s happening in your own hospital, it impacts you differently, especially when you feel like everyone is working hard to provide amazing care.”

But, Dr. Davidson pointed out the findings led to a “deep discussion of the potential root causes” of these disparities, including conversations around racism and implicit bias from providers and nurses. Dr. Davidson stressed the importance of having a supportive department chair who “stimulated those difficult conversations” in a safe and open forum and helped staff feel motivated, “that we’re all working to try and make this better.”

By implementing the aforementioned elements of the bundle and continuously presenting their stratified data, Dr. Davidson said they reduced severe maternal morbidity from obstetric hemorrhage and eliminated disparities therein, over the last year. These findings are not yet published but she will be presenting them in an oral presentation at this year’s virtual Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Annual Pregnancy meeting.

Carey Eppes, M.D. is Chief of Obstetrics at Ben Taub Hospital in Houston and TexasAIM Faculty Medical Director, said that the COVID-19 pandemic has increased the recognition that social and structural barriers are critical contributors to clinical outcomes. Dr. Eppes says instead of labeling patients as “non-compliant” when they do not show up for appointments or abide by certain treatments, hospitals can measure, track, and address the barriers some patients face when getting health care.

At Ben Taub, she and her staff are working to incorporate assessments of social determinants into their health screenings with the goal being to build the screenings into their electronic medical records system. Dr. Eppes says they are currently piloting social determinants assessments for high-risk patients referred to one of their prenatal clinics that houses a social worker: “Right now, I’ve matched it to the days where I have a social worker who can help link to resources. We are trying to expand that to every day of the week, with those patients who have needs identified being able to immediately connect with a social worker for the appropriate assistance and referrals.”

Dr. Ghartey says initiatives to better support Black moms who deliver at Ascension hospitals are emerging through the Ascension Texas Council on Racial Health Equity (ATCORHE), co-founded by Tiffany Ricks, Ph.D., RN, and Elizabeth Polinard, Ph.D., RN. ATCORHE prioritizes community outreach efforts to achieve health equity in their service area through “proactive evaluation” of the health care system. Recently hosting a “meet and greet” panel with staff and community groups, like Black Mamas ATX and Mama Sana Vibrant Women, which led to a dialogue about biases and perceptions between the two groups.

Ricks said she and Polinard recognized early on “the need to engage strategic community partners, such as doula groups or service providers, as a means to build and sustain trust among vulnerable populations in our community, strengthen strategic partnerships, and align missions and goals focused on health equity.”

Now is the time to recognize the “difference between equity and equality,” says Dr. Davidson at Texas Children’s Pavilion for Women, in which care and treatment will vary by patient needs: “That’s the difference with equity: figuring out what our patients’ unique needs are to give everyone the same outcome. They’re not all going to have the same outcome with the same exact treatment.”

DSHS recently launched the newest bundle for TexasAIM, severe hypertension in pregnancy. TexasAIM kicks off its first learning session for the bundle in early April and is now recruiting hospitals to participate. Dr. Manda Hall at DSHS says a bundle for opioid use is on the horizon, and they have been working with early adopter hospitals since 2018. “We’re now working to develop resources and an implementation framework and toolkit, with plans to launch the first wave of a learning collaborative for that bundle with early adopter hospitals in spring of this year.”